“An interesting aspect of Estonian culture is that we do not have a European-style, long-standing tradition of classical music. Our musical activities started to become relevant only in the last 100-200 years and gained speed after our country achieved independence. This may be the reason why, conventional concert halls aside, new ideas surfaced freely and musicians turned to other outlets to express themselves through music.” I am talking to cellist Theodor Sink, one of the outstanding musicians of his generation in Estonia. It’s late at night for him and early in the morning for me, due to our different time zones, and the 28-year-old from Tallinn is talking from his cello studio, which appears to be an attic; his friendly, casual demeanour makes our conversation easy and informative. I was keen to talk about his musical background and the situation of the arts in Estonia, since it emerged from behind the iron curtain in the late 1980s. “In the distant past, Western music sounded distant and exotic to people in the Baltic states and, over time, our composers and artists had to discover their way of creating something that is their own,” he continues. “As a result, our newly emerging traditions were influential in forming the development and music-making of young musicians. This perhaps explains why, despite the small size of the country, I find it most inspiring to work in Estonia.” Sink was offered his first job as Principal Cello of the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra. The procedure to fill such valued positions is different in every country. “At the time, for some reason, interest about the position was not substantial. As very few people heard about it from other countries, only local people applied for it. Admittedly, in previous times, only Estonians were able to secure such positions in our country but that has changed.” Surely, nowadays, this would not be the case anymore. He only partially agrees: “While we would prefer to attract local talent, it has been recognised that if someone from a different country plays best in an audition, appointing that person actually has a positive influence on the musical circulatory system.” World-wide, the lives of orchestral musicians changed dramatically during the pandemic. “Our concerts are regularly broadcast online. We have a method according to which the orchestra is split into two groups. If someone gets infected in the first group, the other one can take over and the concerts can still go on. In Tallinn, our capital, live concerts with an audience are not allowed at the moment.* However, outside of the capital the situation is much better and concerts are open to audiences.” “Let me give you a few examples,” he continues. “This week we are doing recordings. In February, some of us will be performing chamber music concerts, while others will be organised into a small orchestra and they will play concerts for children.” Playing for young audiences leads us to the topic of music education and concerts in general in Estonia. “Our music education is constantly improving but it is linked to which political party is in power. In pandemic times we were lucky that our minister of culture helped keep our concert venues open as long as possible and advocated for the financial development of culture in Estonia.” About concerts, he says: “In Estonia, it is relatively easy to organise concerts. There are many possible venues, though some of them – such as renovated old factories – were not originally intended to become concert halls. These, however, offer a unique experience with their ‘underground’ atmosphere, which suits contemporary music concerts.” Contemporary music seldom attracts huge audiences. But Sink thinks otherwise. “Because of the newly established cultural traditions that I mentioned before, the attendance of our concerts is excellent and not limited to just one particular age group – a phenomenon quite common in other countries. People of various ages, including many young people, visit our concerts, which is most reassuring.” I read about his strong feeling about the importance of physical exercise for musicians. “But of course,” he explains. “Practising many hours a day can be physically exhausting and musicians have to be prepared for that. In the last few years, I have discovered the benefits of regular visits to the gym. I have trouble sleeping and after a thorough workout at the gym, I also sleep better. Of course, according to the commonly voiced theory, straining your hands and fingers can have a bad influence on the flexibility of your playing, but I found that to be untrue. One should simply use common sense not to overdo exercise. I find walking and swimming equally useful.”

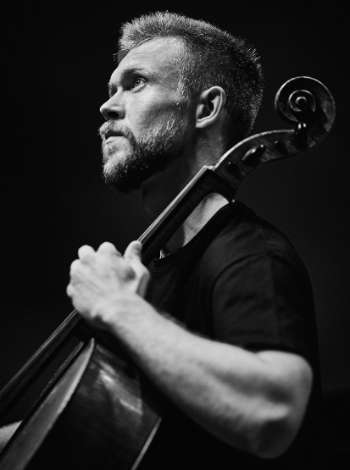

Theodor Sink at the 2020 Parnu Music Festival. © Kaupo Kikkas

Late last year, he performed the complete set of Beethoven Cello sonatas, together with pianist Kalle Randalu. They were the first Estonian musicians to play all the five sonatas in one concert. “About a year ago, my pianist partner invited me to participate in this project. He has played these works several times before and it was truly inspiring to work with him. Previously, I had some sort of fear of these masterworks and I learned only one of the five sonatas, so it was a great opportunity to take on the whole cycle.” “It was a tremendous experience. I prepared the cello part on my own for about two months, and then Kalle and I worked together intensely for about a week. Our meetings were not really rehearsals in the traditional sense of the word. Rather than verbally discussing different ideas, we communicated with each other through our music-making. We both listened to the other’s musical suggestions during playing, and our musical concept evolved almost without trying.” Sink has a reputation of being a fervent advocate for contemporary compositions. According to him, the music of our times has an important place in this world, notwithstanding the problem that with so much new music written, it is often difficult to distinguish between what will stand the test of time and what will not. This is of course a historical problem, which has always been present in previous centuries as well. “One of my teachers, Leho Karin, often emphasised the importance of being open to the music of our own era. If people do not look at new music with interest, they miss out on the rewards of learning the latest of inspired people’s compositions. That is the language of our times and discovering it is just as important as listening to and performing the music of Mahler or Brahms.” Discovering new music is just what he did with his first CD recording, performing Lepo Sumera’s Cello Concerto. “That was all the more interesting because I did not even know the concerto,” he laughs. “Paavo Järvi, who was a friend of Sumera, recommended it to me. At the time, only David Geringas played it, so there was room for a new recording. It is a truly Estonian piece, full of melancholy and eerie melodies, something you have to hear to appreciate fully, and it grew very close to my heart.”

When making a CD recording, every note has to be perfect. I was wondering if that need for perfection was a problem for him. However, as he explains, it was actually a live recording, with a couple of small extra takes beforehand. “A live recording has a completely different feel from a studio recording because in the studio you always feel assured that you can play any parts again if necessary. But this knowledge can ruin the spontaneity of the experience. In a live recording, there may be a few minor slips, but the atmosphere is different, something that a studio recording cannot match.”

Given his enthusiasm about contemporary pieces I asked him to name a few compositions that he thinks will stand the test of time. He lists mostly pieces that he played himself: The

Sept Papillons for solo cello by Kaija Saariaho (“That is very dear to me!”),

Mania by Esa-Pekka Salonen. He also highly values

Ascending. Descending. by Liisa Hirsch for solo violin and chamber orchestra. At the end of our conversation, Sink entertains a dream situation: what would he do if he could do anything in his musical life, whatever pleases him? “Oh, what an opportunity that would be! According to an old Estonian saying, ‘You cannot get rich by working’. So, I would not focus on getting rich,” he tells me with a bright smile. “Most importantly, I would like to meet some musicians – not even necessarily the most well-known ones – whose music making I find the most appealing. For example, I would love to work alongside Nicolas Altstaedt. I have already played once with pianist Víkingur Ólafsson but I would like to repeat the experience. Another of my dream encounters could be with Jean-Guihen Queyras..” “Apart from that, I would love to perform some concertos, new music that I have not had the chance to perform before, such as

Tout un monde lointain by Henri Dutilleux, Pēteris Vasks’s First Concerto or Dmitri Shostakovich’s Second and others. Being open towards this repertoire is so important! I cannot know in advance what that new composition will be like, but I want to give it a try and then decide for myself.” —-

With the Young Artists To Watch project Bachtrack aims to shine a bright spotlight on deserving artists from all over the world that might not be getting as much visibility as they would have without the limitations caused by the pandemic. Find out more about Theodor Sink: Official site | Youtube | Soundcloud

*The information about restrictions on concert hall audiences was correct at the time of the interview. From 1st February, socially distanced audiences in Tallinn have been allowed back into music venues.